Chevron and ExxonMobil Portfolios Overlap Put Mega-Merger Back in Spotlight

July 24, 2025

Exxon Mobil and Chevron's recent major acquisitions raise a provocative question: does the U.S. still need two energy titans, or might it be more efficient for the two to join forces?

An $800 billion combination would certainly evoke memories of Standard Oil, the conglomerate John D. Rockefeller created in 1870 that dominated the American oil industry before the Supreme Court branded it an illegal monopoly in 1911, forcing it to break up into multiple companies from which Exxon and Chevron trace their roots.

Concerns about a new behemoth monopolizing the U.S. energy industry are probably smaller today than in the early twentieth century, given the scale and diversification of the current sector. Nevertheless, a merger of such magnitude would face daunting legal and logistical complexities.

But never say never. Growing volatility in energy prices amid the bumpy global transition away from fossil fuels, shifts in market leadership, heightened geopolitical tensions, and the related rise in resource nationalism could create a confluence of circumstances in the coming years that might make a ‘ChExxon’ merger more than a fantasy.

Waves Of Consolidation

Over the decades, the oil and gas sector has gone through several waves of consolidation largely driven by the need to increase scale, improve efficiency and better enable companies to weather periods of weak commodity prices.

The modern era’s first wave of consolidation followed the oil price crash of 1997, which sparked a cycle of mergers that formed today's so-called ‘Big Oil’ companies: Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies and BP.

The latest consolidation wave, which is centred in the United States, began in 2022 when companies gobbled up rivals to increase their access to high-quality resources as boards shifted their focus to shareholder returns, rather than output, following years of rapid expansion in shale basins.

This included Exxon's acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources for $60 billion, ConocoPhillips' $23 billion acquisition of Marathon Oil and Diamondback Energy's $26 billion acquisition of Endeavor Energy.

One of the biggest deals in this period was Chevron's $60 billion acquisition of New York-listed Hess, which was first announced in October 2023 but completed only last week following a lengthy legal battle with Exxon over Hess' lucrative 30% stake in Guyana's giant Stabroek oilfield.

The Hess deal and Chevron’s acquisition in May 2023 of shale producer PDC Energy for $7.6 billion have also given Chevron’s U.S. production a significant boost.

Global Overlap

Exxon and Chevron's buying spree solidified their position as the largest U.S. producers – and also highlighted how much of their portfolios overlap.

Exxon today produces around 1.9 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (boed) in the United States, of which two-thirds come from the Permian basin, the heart of the shale boom. Exxon expects its Permian production to reach 2 million boed by 2027.

Meanwhile, Chevron's U.S. production is currently around 1.8 million boed when including Hess and PDC. Nearly half of this total is in the Permian, where it aims to keep output steady at 1 million boed through 2040.

Put together, the two companies account for over 10% of total U.S. oil and gas production and nearly 20% of oil and gas production in the Permian.

Shale production requires constant new drilling just to keep output steady. And given that many of the most prolific shale structures are ageing and rapidly depleting, the need for further consolidation in the sector will likely intensify as companies try to improve productivity.

In Guyana, where production has skyrocketed to 668,000 bpd as of March, Chevron and Exxon’s overlap is even more extreme. Despite their recent legal dispute, the two are now partners in the South American country.

Exxon, which operates and owns 45% of Guyana’s enormous Stabroek block, expects its output there to nearly double to 1.3 million bpd by the end of 2027. Chevron now owns 30% of the block.

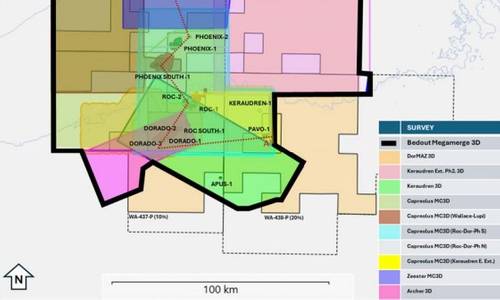

Finally, Exxon and Chevron's upstream portfolios both include significant operations in Kazakhstan, Australia and West Africa – more potential opportunities for consolidation.

Differences Remain

There are still significant differences between the two energy giants, of course.

For one, Exxon has a larger global footprint than Chevron, including a significant presence in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

There also may be a difference of culture, which Chevron CEO Mike Wirth said when speaking to Reuters. Exxon has a reputation for being hierarchical and increasingly litigious, while Chevron is often seen as more engaged with its workforce and partners.

Such differences can be hard to quantify but can indeed complicate large mergers.

The Next Wave

The oil and gas sector appears poised to undergo another round of consolidation in the coming years due to the convergence of multiple trends.

The energy transition will likely lead to greater volatility in energy prices, while increased competition among the oil majors for a shrinking pool of investors could also increase the incentive to streamline operations and cut costs through mergers.

Finally, tensions between the United States and China, and the renewed interest in industrial policy more broadly, could also put pressure on American companies to consolidate ownership of vital natural resources.

And the financial benefits of combining the two U.S. energy giants? It is hard to put a firm number on this given the sheer size of Exxon and Chevron, which have a combined value of $775 billion, but the savings from merging their U.S. headquarters and administrative functions in other countries where they both operate would almost certainly measure in the billions alone. Divestments of non-core assets would further boost the financial benefits.

For context, consider that Exxon expects to achieve $3 billion in savings from its Pioneer acquisition, a company that was bought for a fifth of Chevron’s current value.

This isn’t to argue that the merger is likely in the near future, but the idea shouldn’t be discounted entirely.

And if the merger of the two largest U.S. energy companies were to occur, it would signal – like the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911 – that the industry was entering a new era.

(Reuters - Ron Bousso; Editing by Nia Williams)