Energy Transition: What is an Offshore Vessel Operator to Do?

Philip Lewis

June 20, 2023

The energy transition is moving ahead amid recovery in offshore oil & gas and growth in offshore wind, leaving vessel owners that serve these markets with big questions about energy carrier and energy converter selection for their newbuilds.

What is driving the change?

The foundations of energy transition in the offshore and marine segment can be found at global, regional, national and local levels:

- At a global level, International Maritime Organization (IMO) measures cover vessel energy efficiency (for vessels over 400 gross tonnes) and carbon intensity (for vessels over 5,000 gross tonnes) but do not necessarily impact offshore support vessels (OSV). However, the IMO strategy on emissions is expected to be revised at MEPC 80 in July of this year. Full decarbonization of the maritime sector by 2050 is expected to be discussed but unlikely to be agreed. Measures such as greenhouse gas fuel standards on a well-to-wake basis and some form of carbon pricing are expected to be discussed for implementation through this decade. What we have then is a bit of a moving target.

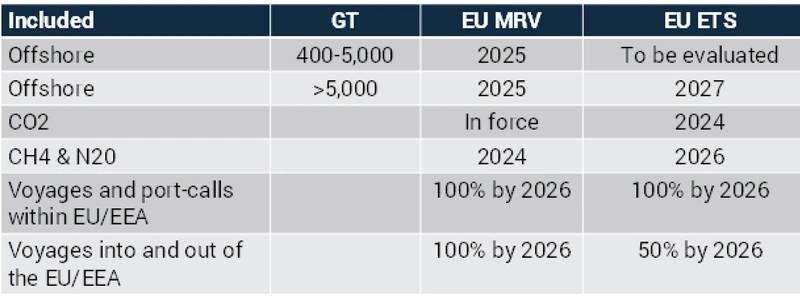

- Currently, vessel movements related to the installation of wind turbines in Europe are not subject to the Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) reporting requirements. However, as our table summarizes, some key numbers for the revised EU MRV and Emissions Trading System (ETS) schemes.

- At a national level, and of importance to floating wind, we note for example Norway’s support of partial or full electrification of vessels or the use of hydrogen and ammonia as energy carriers.

- Now let’s take a local level look within a country. The California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) Commercial Harbor Craft regulation defines emissions standards for vessels calling into state waters and stricter amendments are currently under review. These will likely impact the anchor handlers involved in California offshore wind projects.

Chart courtesy Intelatus

Chart courtesy Intelatus

In addition to these regulatory conditions, we find several other main drivers for choosing low or zero emissions fuels, including:

- Vessel charterers are seeking more and more to manage their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, including emissions associated with their own or chartered-in vessel operations.

- Shareholders in listed companies may demand that vessel operations impact less on the environment.

- Finance and insurance providers in certain markets have become more interested in incentivizing investments that have less of an environmental impact.

- A younger workforce who are increasingly less motivated to choose careers in industries associated with hydrocarbon related emissions, such as oil & gas and marine operations.

What are the choices?

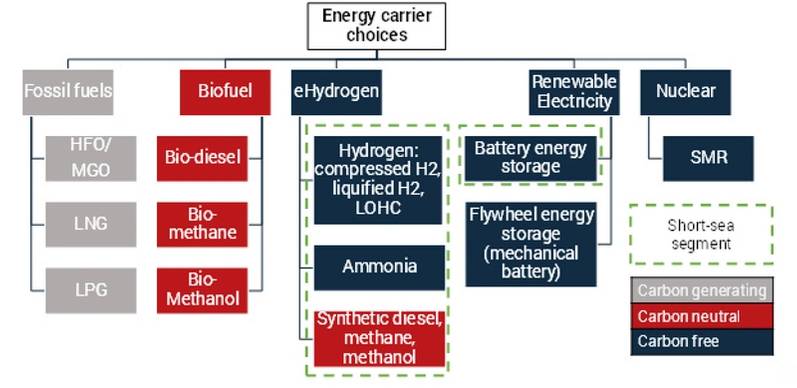

As per the chart below, there are many choices of lower carbon, carbon neutral and carbon free energy carriers, some of which (ringfenced by the green dotted line) can be seen as more suited to shorter sea voyages typical of most of the offshore oil & gas and offshore wind fleet.

Depending on the trade and fuel supply, we see an increase in the number of hybrid energy systems, combining an internal combustion engine (dual fuel for flexibility) or a fuel cell with battery energy storage and shore power connections.

Chart courtesy Intelatus

Chart courtesy Intelatus

And what about the challenges?

The first challenge is to choose the energy carrier(s) and the energy converter for a vessel. This will often be dictated by trade patterns, vessel size, local factors and the availability of internal combustion engine, fuel cell and/or battery energy storage system options.

Securing a supply of fuel is the next challenge. At present, most low and zero emissions fuels are in very limited supply. Further, the scale of most offshore vessel operating companies and trading patterns does not allow most owners to replicate what liner companies like Maersk have done, which is secure 1.4 to 2 million tonnes per year methanol supply from nine supplier partnerships in Asia and the Americas, and continue to review a further 30 partnerships in regions including Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

If you can get the fuel, the next challenge is the cost of the fuel. Carbon pricing, in markets like Europe, will help this situation, but at a fundamental level, green hydrogen, e-methanol and e-ammonia cost more than marine diesel and gas oil.

As many people know, certifying bunker quality is a major challenge today. But the challenge will only become more daunting. Taking methanol as an example, methanol can be produced from coal (brown), natural gas (grey), from carbon capture from another combustion process (blue), renewable sources (green) or nuclear (pink). The final product is always CH3OH. The question is how to ensure that the methanol in the tank is green.

And finally, there are a range of technical and operational barriers ranging from toxicity of certain fuels, lack of sufficient bunkering infrastructure, the impact on onboard storage based on the large volumes required to store hydrogen, ammonia and methanol, available of internal combustion engines, availability of fuels cells and battery energy storage systems and crew capabilities.

What else can we consider?

On top of the energy carrier/converter choice, there remain several other tools for lowering emissions intensity available to owners to consider, depending on the size of vessel. These include:

- Ship design and hydrodynamics: Hull-form, ship size, propulsion improving devices, propellers, rudders & material optimization, air lubrication, hull coating/cleaning and propeller cleaning.

- Energy assistance from wind or solar sources.

- Logistics and digitalization: Speed reduction, weather routing, trim, draft, and ballast optimization, autopilot software, engine de-rating and vessel size.

- Waste heat and/or kinetic energy recovery.

- After treatment measures such as carbon capture and storage.

Copyright AdobeStock/David Maddock

Copyright AdobeStock/David Maddock